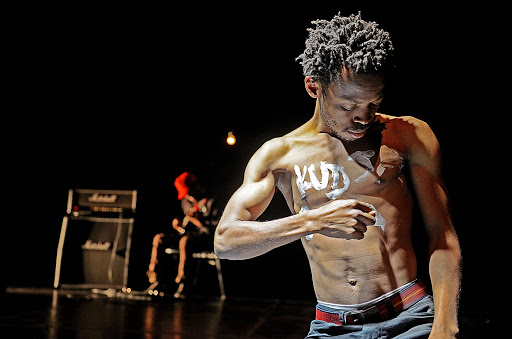

“I Hate Theater, I Love Pornography”, Zoukak Theatre Company

© crédit photo : Vincent VDH

We started the time of exchange by a listening game consisting in counting together until 20, without indications of who takes the floor, and which obliges to be successful to be on the same tempo, the same moment. (If two people speak at the same time, you have to start again). I then took the time to recall what was for me a workshop of reception: “A time of horizontal exchange, which by “alternative” modes of exchange tries to break the vertical relations of a usual speaking: the fact that those who are more at ease with the oral, in English moreover, those having more culture and theatrical legitimacy are those who in normal time monopolize (in spite of themselves) the time of speaking.

The idea is to create a time of connection, even allowing one to feel legitimate in deciphering one’s feelings (which a usual time of exchange can prevent, the question of legitimacy can even prevent one from knowing oneself what one thought of the show).”

To do this, the reception workshop must organize a time of exchange evacuating the word: Each of the participants had to think of 3 words in their native language that had inspired “I Hate, I Love”, possibly adding music, dance movements, a rhythm, a drawing. We then split into two groups of 4, with the objective of collectively choosing 3 words synthesizing the opinions and around them begin to constitute a small art form to be returned to the other group.

Group 1:

The first group proposed a kind of choir more and more anarchic.

In a circle, each one in a row, to the tune of “à vous dirais-je Maman” sang a loop in French, English and Spanish. Then in the continuity resumed the first person and started in canon until arriving at a result more and more dissonant and chaotic. They then begin to move separately in the room, with the intensity rising, rising, the words becoming more aggressive, before, without concertation, gradually coming down as the fatigue rises. From my point of view: This proposal synthesized a cocktail of emotions, energies (the ritual side of the song in particular) that Zoukak diffused with I Hate I Love. The tune of “À vous dirais-je Maman” reminds us of the children’s songs of the show, with this particular irony. Moreover, the group decided to put themselves in the place of the actors who were deploying a mass of energy (banging on the floor, singing, blowing, for about twenty minutes at the beginning, about twenty in the middle).

Group 2:

After thinking about the terms inequality and truth and trying to represent these concepts with a chair as a base, we decided to create a small game of “inequalities”.

of “inequalities”. Each participant had a chair, which could be folded, and the 4 participants tried to create a structure with the 4 chairs, but finding it impossible to agree, they split up. The music starts, the game begins.

The rules: everyone is seated on a chair, when a seated person claps twice (at once, in succession, or with the clap of another seated person), the participants must change chairs and can when seated try to steal a second or even a third chair.

It is possible when you have two chairs to open the second and simply switch positions, but the “chairless” are on the lookout.

The chair here represented “a truth/voice”, which when accumulated (by a power, a state) constitutes a power, and when lost prevents one from expressing oneself, from acting (explaining why without a chair, the participant lost his/her power of rotation).

For those who have lost their voice, there are only small, risky windows of opportunity left, in which one must try to trick one’s way back to voice.

The idea was to highlight the inequality, the power, through the irony of the game (Emma pointed out that Zoukak used the same register).

We then took the time to explain the two proposals, to go back over them and finally to go back individually on our own words and their place in the common proposal. At the end of the workshop, I had the impression that I knew what the other participants had thought of the show, without at any point having had a real time for organized exchange.

Félix Vannarath